Terrible Turing Machines - Season 1

- Published on

- ∘ 15 min read ∘ ––– views

Tags

Previous Article

Next Article

Preface

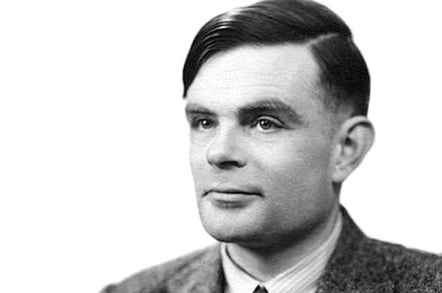

The Man

The British mathematician and father of modern computing Alan Turing was born in 1912. Popularly lauded as the brains behind cracking the Nazi's code used in the second World War through the use of his Enigma machine, Alan Touring dedicated is life to computation. In 1936, he published an essay "On Computable Numbers, With an Application to the Entscheidungs Problem" which hinted at the ultimate focus of this series of blog posts: Turing Machines.

The Machine

In the aforementioned article, Turing describes a machine which would supersede human computational capabilities:

We may compare a man in the process of computing a real number to a machine which is only capable of a finite number of conditions q1, q2, ..., qR which will be called “m-configurations”. The machine is supplied with a “tape”, (the analogue of paper) running through it, and divided into sections (called “squares”) each capable of bearing a “symbol”. At any moment there is just one square, say the r-th, bearing the symbol S(r) which is “in the machine”. We may call this square the “scanned square”. The symbol on the scanned square may be called the “scanned symbol”. The “scanned symbol” is the only one of which the machine is, so to speak, “directly aware”. However, by altering its m-configuration the machine can effectively remember some of the symbols which it has “seen” (scanned) previously. The possible behaviour of the machine at any moment is determined by the m-configuration qn and the scanned symbol S(r). This pair qn, S(r) will be called the “configuration”: thus the configuration determines the possible behaviour of the machine. In some of the configurations in which the scanned square is blank (i.e. bears no symbol) the machine writes down a new symbol on the scanned square: in other configurations it erases the scanned symbol. The machine may also change the square which is being scanned, but only by shifting it one place to right or left. In addition to any of these operations the m-configuration may be changed. Some of the symbols written down 232 will form the sequence of figures which is the decimal of the real number which is being computed. The others are just rough notes to “assist the memory”. It will only be these rough notes which will be liable to erasure.

Turing goes on to elaborate on the exact specifications of the theoretical machine which I strongly encourage readers to pursue themselves. But for the sake of the musings of this series, the layman's definition of a Turing machine can be understood as an infinitely-long tape (memory) with initially blank squares that can be written to.

The operational aspect of the machine has 3 functions:

- Read the symbol at the current square (memory address),

- Write/overwrite the symbol at the current square,

- Move the tape left or right by one square.

The last piece of vocabulary we need to embark on our Terrible Turing Journey is "Turing Complete." Something is said to be Turing Complete if it can simulate a Turing Machine. If something is Turing Complete, it could theoretically solve any computational problem it was given, provided sufficient run time. Real world scenarios are limited by their lack of an "infinite memory tape" alluded to in Turing's paper - hence the thought experiment remains in the realm of goofs, gaffs, blog posts, and academic shit posts (commonly referred to as mathematical papers).

Tom Wildenhain has an excellent shit post and accompanying hilarious presentation on the Turing Completeness of MS PowerPoint.

The Plan

Now that the groundwork has been established, we can have some fun. The purpose of this blog, from my perspective, is to house a series of Terrible Turing Machines.

Enjoy

Episode 1: The Tornado

According to the Fujita scale, no matter how unlikely, it is not impossible for an F6 "Inconceivable Tornado," whose wind speeds could reach up to 379 mph, to produce fast enough bouts that the small area affected, along with the mess produced by the underlying F4 and F5 winds, would be irrecognizable.

Whereas commonsense would immediately draw one's mind towards the destruction caused by the "missiles," –namely cars, refrigerators, lamp posts, etc.– I'd beg the reader to consider the creative possibilities of the high-speed winds. This is not to downplay the ultimately destructive capacities of such a natural disaster - rather a contemplation of the pseudo-impossible. While F6 hurricanes are dubbed "inconceivable," it is not inconceivable for an arbitrarily long, dare I say...infinitely long? tape, along with various mechanical components, to be forced together by the violent winds in such a way that the resulting mass could imitate the functions of a Turing Machine.

Perhaps it is inconceivable, but humor me.

This would be, without a doubt, one of the worst ways to go about assembling a Turing Machine - beat out in this manner perhaps only by its cousin, the hurricane.

The Hurricane

Operating on a separate scale to measure wind speeds known as the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale (SHSS), hurricanes achieve markedly-lower wind speeds than their landlocked counter parts. That being said, there is no objective "minimum Turing velocity" needed to achieve the assembly described above. We merely assume that the higher the velocity, the more chaotic the movement of the shrapnel. The more chaotic the movement, the more difficult it is to disprove that such a pattern that would construct a Turing Machine would be impossible to achieve.

With this artificial constraint of hurricane wind-speeds in mind, we can note that, according to the National Hurricane Center, a Category 5 hurricane is defined as exhibiting sustained wind speeds of 157 mph or higher. Note that the keyword "higher" allows us to benefit from equal amounts of entropic infallibility as the argument made for Tornado Turing Machines. Quite high speeds indeed.

This method of assembling Turing Machines is even worse than relying upon a tornado as, even if the winds do somehow manage to spin together a Turing Machine, the damned thing would get soiled in minutes by the accompanying torrential water forces inherent to hurricanes!

Conclusion

I assert, with some degree of confidence, that relying upon natural disasters is a terrible way of making a Turing Machine.

Episode 2: Two Frogs

Episode 3: Chemicals and Fruit by the Foot

Suppose that an individual consumes random combinations and quantities of chemical substances which are known to react with each other to form solid particulates inside the . Suppose that same individual has unfettered access to Fruit by the Foot.

You may see where this is going –as well as is chemical pseudo-impossibility– but bear with me.

If, before the Turing Tummy Test Tube poisons himself, he is consumes the perfect mixture of of chemicals to synthesize a metallic alloy that A) does not rupture his internal organs do to heat generation and B) reacts in such an interaction with his tummy-tum-tum that a tape could be passed through the metallic formation, then I dare say we may have a Tummy Turing Machine on our hands!

A cursory look at a list of toxic chemical compounds indicates that this means of creating a Turing Machine is pretty terrible!

However, if we were to luck out (something that is excruciatingly necessary for many of these methods), and were then able to pass Fruit by the Foot through the esophagus, and down through the metallic Turing chassis - all we would need to accomplish at this point would be a means of reading and writing to the strip.

Luckily for us, Fruit Roll-ups have been developed with literacy in mind. Rather than writing from the Turing Machine to the tape, we could instead perform an inverse process to achieve a similar output; by writing from the Tattooed Fruit Roll-up to our Turing Machine (erasing, rather than writing) we could achieve a functionally identical means of read/writing.

A Question of Memory...

Although we lack the means of writing to our "tape," the aforementioned unfettered access will allow us to simply override necessary computational values to memory further down the line. With each instruction to read/write/access our tape, we must append another command to duplicate this command at a given address a necessarily large distance down the fruit by the foot before returning to the initially specific address.

I really don't know how this means of usurping read/erase-only memory access would happen without memory... But I'm fairly certain it is possible, and is therefore left as an exercise for the reader.

If one manages to survive the self-induced poisoning (in the name of science!), and overcome this puzzle of writing to a Fruit Roll-up with no means of writing then that person would have discovered a Truly Terrible way of making a Turing Machine.

Episode 4: Isomorphic Relationships

Once again phoning definitions out to Hofstadter, we can understand isomorphisms as meaning-preserving mappings between two complex structures.

"[An isomorphism is] defined as an information preserving transformation. We can now go into that notion a little more deeply, and see it from another perspective. The word "isomorphism' applies when two complex structures can be mapped onto each other, in such a way that to each part of one structure there is a corresponding part in the other structure, where "corresponding" means that the two part play similar roles in their respective structures. This usage of the word "isomorphism" is derived from a more precise notion in mathematics."

We can use isomorphisms to formulaically crank out Terrible Turing Machines!

- Take one complex structure to be a Turing Machine,

- Take a second complex structure to be absurdly disparate from Turing Machines,

- Do some grunt-work of asserting the isomorphic relationship between the two structs,

- Describe why you've done a terrible thing

Let's Try it Out!

Wood Peckers are Bad Turing Machines

- The eponymous drumming performed by woodpeckers is a non-vocal method of communication utilized by several members of the Picidae family. Ornithology tells us that each species of woodpecker exhibits a unique pattern and frequency of wood pecking that the fowl use to court females and establish loose territorial boundaries. Although their name presupposes "wood" to be the material of choice, these birds are by no means precluded from head banging your gutter or any other percussive structure they deem fit. Because woodpeckers' concussive efforts emit a predictable, measurable, and intentional noise, we, as third-party observers, could assign arbitrary values to the drumming patterns performed. If we could establish "code" as simple as binary (which is implicit to nearly any isomorphic pattern we will identify: things are either happening, or they are not. A truly impressive code.), we could imitate the behavior of a Turing Machine according to the drumming of the woodpecker - the efficacy of which would be improved in relation to the complexity of the "language" we develop/translate the pecking into.

- This is obviously a terrible idea as we bear little-to-no control or means of communication with woodpeckers. Therefore, the processes undertaken by this isomorphic Turing Machine would be quite erratic. What a Terrible Turing Machine!

This Terrible Turing Idea was brought to you by Patrick Riley.

Episode 5: Rube Goldberg

A shit poster of some renown - the American cartoonist Reuben Goldberg was known for his intricate and convoluted blueprints for elaborate gadgets that ultimately accomplished nothing. Famous in his own life, the illustrative genius pioneered an entire genre of entertainment focused on pursuing the most roundabout or unnecessarily difficult means of achieving something.

Before we become overwhelmed by the isomorphic rabbit hole which beckons us from the crest of next week, I thought that it would be fun to momentarily diverge from and indulge in a sillier Thuring Thought experimenth.

The Machine

The year is 1955.

that a tennis ball rests atop a hill looking down upon rural San Francisco. A gust of wind rocks the ball forward, ever so slightly, causing a single domino to topple over. Immediately adjacent to the falling domino lies another, and another, and another! Spiraling all the way down the hill, dominoes coil around the underbrush, constricting the non-Turing Complete organic matter. For twenty-two and a quarter days, the dominoes clink into one another. And only once did the next domino not fall over when it was supposed to causing our unnamed observer to dash from his cover and resume the process!

Once the last domino topples over barrier separating desolate soil from smoothly paved concrete, it lands on a scale, attached to which is a string stretching upwards and over a house, through a complex pulley system that has been fully containerized such that if the string breaks free from any one pulley, another will immediately get shuffled into place to catch it.

After the domino comes to rest on the scale, the rope is tugged just enough to cause a thunderous T W A N G that be heard from the back yard. As our third-party observer scrambles to race around to the back, more mechanical whirring and clicking can be heard as a tesseract of levers, string-pulley systems, dominos, actual bells & whistles, and catapults manufactured out of commonplace silverware.

It is a scene of chaos as glasses of colored liquid are toppled into miniature pipelines, ball bearings race each other down tracks - displacing hammers, that were balanced perfectly upright, into downward trajectories to continue the domino effect. With each motion, another is set into place.

The observer is prepared to make a pseudo-big-brain assessment about the potential for isomorphic mappings of the mechanical behemoth that has been hidden in the backyard of who he can only assume to be Mr. Rube Goldberg himself. However the observer is naive and STUPID STUPID STUPID - BHoag is almighty, and BHoag knew the observer would be so foolish as to make such an irrational assumption. No, it cannot be isomorphically mapped to a Turing Machine, or maybe it can, who cares?! Instead, the final domino tips off a ledge, landing on a trigger pad which ignites the fuse of a canon aimed directly at Rube's backdoor.

At this very moment, Rube Goldberg emerges out the back entrance, visibly perplexed and awestruck by the simultaneous beautiful and Lovecraftian monstrosity that is the machine erected in his backyard. The canon fires! A net lined with weights shoots out at the now-aged man bringing him to the ground - immobilized. BHoag walks over him, attaching a rope to the tangle of nets that now entraps him.

BHoag surreptitiously snarls at the inventor.

The old man surrenders, and produces a Turing Machine, bending to the will of BHoag and creating a Terrible Turing Machine under truly Terrible circumstances.

Episode 6: The Infinite Properties of Physical Displacement

The inevitable movement that transpires through popcorn kernels when heated to the temperature of 100 ºC, causing them to _ pop _ contains several observable and, more importantly, measurable properties.

From the the simple scalar values alone, we can appreciate displacement, speed, surface area, weight. Accounting for the vectors: velocity, acceleration, angular velocity, and angular acceleration.

Suppose we were to pair the displacement before and after the popping of the kernel, along with the angular acceleration vector . There exist sufficient permutations of the infinite combinations of these two values that we could isomorphically map each value and furthermore each combination to functions of a Turing Machine. For example, a displacement of 0.14 meters and an angular acceleration at time could be associated with the Turing commands "Left 1, Write B1:0x00f8a."

Although the domain of displacement values and angular acceleration vectors is relatively limited due to the maximum limits of values achievable only by heating kernels, there exists sufficient values and combinations that we can assert that, no matter how terrible, popcorn is Turing Complete.